Wet end

The Holden Vale Bleach Works in 1975 was a simple place. One raw material – cotton linters – one product – cellulose – provided in two forms of packaging: block and sheet. The process that transformed the raw material into the product was pretty simple too – wash, bleach and dry.

One set of tubs for washing and bleaching everything that came in through the devil hole, and then wet white cotton pumped either to be dried and pressed into blocks, or laid on a paper-making machine to be rolled up as sheets of thick blotting paper.

Very little was automated. The big tubs were filled and emptied with the simple control of a 20 foot long wooden dipstick. Pumping to one or other output process was simply a matter of the team running that process calling the keeper of the blend tub – “Pump some!” (And I mean calling - just shouts across the factory.) And then “Stop pumping!” (and therein lies a tale – later). This is not high tech; this is a factory that hasn’t been touched since it was built sometime in the 1920s, I guess. The gap between “Pump some!” and “Stop pumping!” is a matter of handed-down knowledge – just enough minutes to supply the need which has been the same half-a-dozen times a day every day for the 21,000 days since the factory was built.

The “wet end” is the wet end of the highest tech process in the factory – the paper-making machine. Clean cotton suspended in lots of water is pumped to a holding tank about 25 feet off the ground from which it runs off evenly and gently over an 8 foot wide lip into a long shallow bath with a moving bottom conveyor made of fine wire mesh. The flow of water down the bath keeps the layer of cotton moving, and as the water drains away, the layer forms a wet deposit on the moving mesh.

The nascent paper, forming as an even film on the mesh conveyor as the water drains out of it should be just coherent enough to transfer (carefully!) an inch or so down and across onto another conveyor, this time of felt. Hot air dries the cotton mat as it passes along on the mesh until it spills over as the mesh belt doubles back. What spills over has some integrity as a damp mat, and it drops an inch or so down and across onto another continuous band, this time of felt.

The felt of which the second conveyor is made has a very even surface which transfers into the smooth surface on the forming paper. (This surface is created by the urea in which the felt is pounded during its formation - this is the finish that used to be created just round the corner in Higher Mill - I alluded to this in my discussion of toilet matters.) The forming paper is dried with heat as it is conveyed along, forming something closer to a wide ribbon of paper, with the beginning of a paper’s strength.

At the end of the felt (where that band doubles back) the sheet drops, maybe an inch or so, onto a big heated roller (maybe 7 foot in diameter, 8 foot wide), turning slowly to carry the paper along.. This second transfer is another vulnerable point in the process. The surface of the roller has to be turning at exactly the same speed as the paper coming down the felt runway. The forming paper has to be dry enough to cohere, but wet enough to be flexible. If everything is right, the paper, maybe 8 feet wide, will cross the inches of space between felt conveyor and roller and be carried on steadily round the roller and on to three or four rollers in turn, the heat diminishing as it passes.

What comes off the end is a continuous sheet of the consistency of blotting paper, which is either rolled up for shipment, or put through a cutter for those customers whose factory processes demand sheets of cellulose.

The technological demands are fairly obvious. The rollers have to be going at exactly the same speed, or they will tear the paper. The speed of the rollers, picking up the wet paper needs to match the speed of the felt band which needs to match the speed of the wire mesh band. The gradation of heating (drying) through the process needs to be right within fairly close tolerances. And so on. Not exactly high tech – but higher tech than anything else in this factory.

And some art, too. How the cotton wash slops over onto the start of the production line determines how evenly the cotton will be laid and therefore the consistency of the paper produced. Taking the wet mat from the wire mesh onto the felt is a delicate process, and so from the felt onto the rollers. Even drawing paper from roller to roller demands some care. After a break in the production (an accidental tear, or something deliberate) the wet end man comes into his own, with the chance to put production back on again in a few deft steps, or to lose production as the paper tears or collapses over and over.

An honour, therefore, for me to have been made a wet end man, after 11 months mostly wrapping blocks of cotton in brown paper and 3 months absence teaching developmental psychology at Cambridge.

I was never the wet end man, though – just a wet end man; assistant to Donald. Now, Donald – there’s a few stories.

|

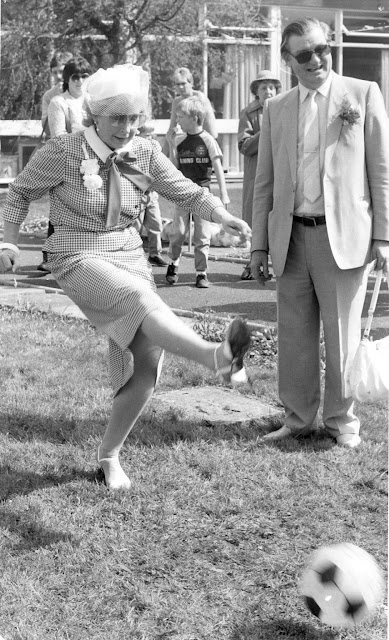

"The Bleach Works" (Click over to enlarge)

Photo kindly shared to us by Alec Taylor |

Donald

I presume that Donald must have had many episodes of working at Holden Vale, or maybe he had been a steady employee some time ago. He was a recognized master of the wet end, and he had to have learned that sometime. He turned up after I had been in Holden Vale a few months, and stepped straight into the wet-end job. But he carried the air always of someone who was not going to be with us for long, and who would give no warning when he wandered away.

He was one of the very few people I connected with in that place for the years I was there. Which is, superficially odd, because Donald was one of the most unconnected people I have ever met. He was a gypsy. (That may not, nowadays be a politically correct word to use, but in this case it is the mot juste - it encapsulates perfectly Donald's lack of investment in the practical here and now and the sense he exuded of being transitory.) For all I know, he might actually have been a Romany – he didn’t sound like a Lancashire man. What I meant, though, was that he moved among us like a gypsy. Always a few days growth of stubble. Odd that – for a period I saw him up close every day. You would have thought that I would see him after he shaved, or else I would see a beard grow. The perpetual two-day growth was just one of the mysteries.

The sense of connection that emerged for me with Donald was one of mood and empathy with his detachment. I know I recognised him in this; I came to believe that he recognised me. His detachment was life-long, or at least by the time I encountered him it seemed so. At that stage, I did not know if my detachment was life-long, but I was beginning to fear it was so. In me, it was my separation into an unreachable mental state that detached me from the world. God knows what it was in Donald - upbringing? deprivation? some sort of madness? even a spiritual state, whatever that is?

Donald always wore a jacket. Greasy and old, with a torn pocket, but it contributed to his air of dignity. His hair was mostly grey, on black, and straight. Quite long (maybe collar length) and always combed across his head. He was quiet, hardly talking to anyone. The guys who had been in the factory forever respected that. They did not try to engage him in conversation – they gave him a respectful distance. And Donald put the newer guys effortlessly in their place if they accosted him. He had presence.

I joined Donald when I was promoted to being second man on the wet end, after a longer stint on the base-level folding job than most employees. The label “student” sticks hard, and one of the things it meant was – “don’t promote, he's not staying long”. Ironically, it was after I had come back from a three monthe gap, when I was lecturing at Cambridge, that they decided I could move on.

The wet end is one of those jobs like being an anaesthetist or an infantryman: mostly long gaps of inactivity with occasional bursts of panic. The bursts of panic – planned very occasionally when there was a break between batches, or caused of a sudden by breaks in the paper – were occupied with the business of getting the stream of wet cotton running through until it was a wide ribbon of rolling paper again.

I have given the mechanical description of the paper-making process above. This should be flavoured with a sense of what the work felt like. I don’t want to make too much of it. No-one in that place really cared a damn whether we were productive or not. Nevertheless, there are two of you, standing high up on the gantry where the wet flow begins, responsible for restarting the flow of paper without which all the hands below you are idle - on the rollers, the cutters, stacking, moving pallets and in the warehouse. This does induce a sense of responsibility, even urgency.

When restarting is hampered by cotton that won’t flow smoothly, and tears appear between the conveyors or between the felt and the roller, between the rollers, and so on, then all of these men are not only idle, but sarcastic. If the foreman decides that they should not be idle, but should be busy doing something like cleaning up (usually when a suit is expected to be visiting from the other side – the offices), then the sarcasm rapidly gets nasty.

Working with Donald, I rarely suffered these indignities. Donald always adjusted the flow so the cotton spread evenly; when Donald caught the end of the wet proto-paper and flipped it onto the felt and then onto first hot roller, it always stuck and rolled without a break. I followed behind him, in close and respectful attendance.

As a result, the gaps of inactivity with Donald were long – often a whole shift.

Donald spent those periods, apparently, almost completely without occupation. He would roll a cigarette. He would smoke it very slowly. He did not appear to be looking at anything, but he looked attentive. He would patrol his machinery, occasionally making little adjustments that were mysterious to me both in terms of what they were and what had alerted him to their necessity.

I would read. I could get through two novels in a shift, and make huge inroads into more serious stuff. I read George Trevelyan’s History of England as if it was a whodunit (which it is – or many, many interlocking whodunits), in a series of concentrated bursts.

There was an unfortunate consequence to that particular burst of reading. Absorbed in the Tudors and the birth of modern government, I failed to test for the completion of a batch of cotton pumped over from the bleach tubs. (The test was very high-tech – an 18 foot wooden stick dipped into the tub to see how deep it is.) I failed to call over to stop the pumping. Only when a guy on break, smoking a cigarette in the open air, saw the cotton spilling over from the tub and ran in to shout an alert, did I remember that I ought to tell them to stop pumping.

That one stopped the whole factory. It was the middle of the night-shift, with no management in sight. Tom the foreman, a phlegmatic chap from Duckworth Clough, decided to get the problem out of the way before management came in the morning. He closed down the whole factory, gave every man a shovel, and we shifted a huge pile of wet cotton, stinking of chlorine, from our car park over the wall into the neighbour’s yard. (I am not sure who the neighbour was. It might have been the bottom end of the lot occupied by the candlewick bedspread factory, formerly the Mission Hall, by Holden Tenements. In any case, the yard did not look as if it was in constant tidy use so as anyone would notice any time soon the change wreaked by a few hundredweight of cotton.)

Donald didn’t mind that. He was quietly amused. He liked the fact that I didn’t need him as a source of diversion during the long shifts. He contemplated; I read. It worked comfortably for both of us.

Donald introduced me to his local – the Robin Hood. That was a major act of social grace. We took to meeting there before shifts, and going up to the factory together. I have described this fine institution elsewhere in this book, and recounted the habits of Donald’s breakfast – a pint before the 2.00 p.m. shift, drawn as soon as the landlord saw Donald’s curtains twitch.

Donald lived in a terrace of houses opposite to the Robin Hood, across Holcombe Road. The atmosphere of the whole of that road, below the factory, felt as if it was unchanged since before the First World War. The fabric was unchanged, of course – solid blocks of grey stone stained by water and age, slate roofs, stony ground and a few scraggy sheep looking miserable. Holcombe Road winds in and out beside the branch railway line, and the cottages are tucked in by the railway or lining Swinnell Brook. The Robin Hood is hunched down on the east side of the road, between road and railway and brook, and Donald’s little terrace of six houses was opposite. I guess they were built for the favoured workers at Sunny Bank Mill in the previous century.

The terrace did not look occupied. It was as if Donald was squatting there. It was not just that Donald did not leave much impression on the place he lived in, but one could see little evidence of the other residents either. It was a place that a gypsy was passing through.

I did not learn much more about Donald from this new friendship. Whether we were in the saloon bar at the Robin Hood or up at the back of the gantry by the filthy windows of the factory, we just coexisted in companionable silence. I felt that the quality of the silence was changing – that was my only measure of the friendship. I do not think that there was any externally observable change. But I felt, increasingly, that I was being let into a private space that Donald normally kept to himself. I have to admit that my own mental state must have been a factor in this perception – this was a period of intermittent, but continuing, mania for me.

I am reasonably sure that my intimacy with Donald was privileged. I do not think that he had many others in the factory (or outside) with whom he had the same comfortable, long silences. However, I am also reasonably sure that if I could have had a conversation with him (which was, itself, fairly inconceivable) on these lines, he would regard me as if I was demented – these are lines of thought on which I am sure his mind never travelled.

by Bob (Ex Pat living down South)